>

When an idea and an opportunity come together, it can mean satisfying work. In 2005 I flew to England with a church choir. I noticed benches, both ordinary benches and unusual purpose-built ones. Something clicked. Some yellow locust trees had fallen on our property. Locust is known for resisting rot - people say that if two posts are planted side by side, one steel and one locust, the locust post will still be standing when the steel one is gone. Yellow locust was once a furniture wood but the supply was too small to meet demand and other woods replaced it.

Why not make a bench from the fallen locust? Weavers have "sheep to shawl" events, so this could be "branch to bench." Here was a chance to mill the wood, make the parts, and use the result right where the trees had grown. A brick circle in a new landscaping project looked like the perfect spot for it. My collection of tools and woodworking experience finally looked large enough to do this kind of work.

Why not make a bench from the fallen locust? Weavers have "sheep to shawl" events, so this could be "branch to bench." Here was a chance to mill the wood, make the parts, and use the result right where the trees had grown. A brick circle in a new landscaping project looked like the perfect spot for it. My collection of tools and woodworking experience finally looked large enough to do this kind of work.

Chances are there's nothing in this project that you haven't thought of doing yourself. It may inspire you to try one of the "what-ifs" bouncing around in your head.

Benches and chairs are two of the most satisfying things you can build. They're useful. They can be beautiful. While we put our stuff in boxes, bowls and bureaus, we put our whole selves in benches and chairs.

And benches are all over. You've heard of deacons' benches, stadium benches, park benches, and mourners' benches (not to mention workbenches, which are really tables). American coaches can bench a player, and members of a parliament may be back-benchers. Walt Whitman wrote of the place "where bee-hives range on a gray bench in the garden, half hid by the high weeds," and Wordsworth of the "cottage bench or well-spring where the weary traveler rests."

Benches invite us to stop and sit. They seem to say have a seat, take a load off, 'bide a wee, rest your feet. Making one, using it and seeing people sit on it is rewarding.

Every project is an experiment. I never made a bench or designed anything with this many parts. It would be a new experience to cut the stock, create a one-of design and make more than 40 mortise and tenon joints.

PLANNING

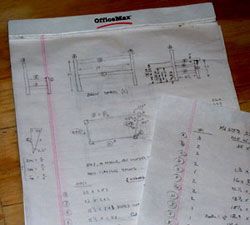

The work began with a sketch. Taking stock (so to speak) of the logs on hand, I let the wood control the design. Its size, shape and quantity established the bench's length, the fortunate curves of the front and rear legs and the sizes of some parts. Think of this design philosophy as "sufficiency," not perfection. I wanted the bench to be good for its job, which is to seat one or two people comfortably and stand up to the weather. It's a natural approach to design and it fit the purpose.

The work began with a sketch. Taking stock (so to speak) of the logs on hand, I let the wood control the design. Its size, shape and quantity established the bench's length, the fortunate curves of the front and rear legs and the sizes of some parts. Think of this design philosophy as "sufficiency," not perfection. I wanted the bench to be good for its job, which is to seat one or two people comfortably and stand up to the weather. It's a natural approach to design and it fit the purpose.

On a piece of quarter inch plywood I drew a full sized pattern of the bench ends, the parts with the arms. These were the complicated assemblies and this forced me to draw the joints involved. Since the project stretched on for several months with many interruptions, the pattern was a reference whenever I started work again. I've since read that a famous school of cabinetmaking has its students do a full sized pattern for every piece of furniture they make.

To be sure there was enough stock I wrote check lists, marked pieces, set them out in order and made lists again. With so many parts there was no way I'd remember what I wanted to do with any one rough piece.

To fit in the brick circle, the bench was designed to bend with an included angle of 155 degrees. The angle made me haul out high school trigonometry so the seat depth in the center would let the front and back edges be parallel. That is, the seat is about an inch deeper in the angle of the bench than at either end because the center rail is in effect the hypotenuse of a triangle.

TOOLS, METHODS AND FINISHING

Split and chain sawn, the rough stock sat in the garage to dry. Indoors it would have dried too much, because the bench is outdoor furniture. After several months the stock was dimensionally stable.

Resawn, which means logs turned into lumber, made good use of the sixteen inch band saw I bought from its previous owner last year. The big saw is no weakling but in dense locust four or five inches thick it still cut slowly. Part way through the work I replaced the old blade with a Wood Slicer band saw blade from Highland Hardware and the improvement was dramatic. Immediately the saw cut easier, faster and smoother.

From dried, rough pieces the jointer and portable planer produced stock for each part. Since the design was in part driven by the available wood, I found myself going back to these tools many times.

There are lots of ways to cut mortises and tenons. Here the plunge router was a good tool for mortises. The part to be mortised was clamped to a simple homemade wooden template. With a template guide bushing and a spiral upcut bit the router made the job quick. To cut tenons I went back to the band saw, always leaving them a little fat and trimming later. Big mortises and tenons engaged lots of wood in the joints.

Sharp chisels were crucial. They let me clean and adjust the mortises and tenons. (If you've never sharpened that chisel of yours, do it even new from the store they aren't truly sharp.) My wife got used to occasional pounding noises from the basement and my ears got used to the earplugs and earmuffs.

The bench sits outdoors and "finish sanding" started and ended with a 60 grit disk on the random orbit sander. To round the arm rests I experimented with a coarse flap disc on an angle grinder. That removed lots of stock very quickly but was harder to control.

Locust is so durable that I'm leaving the bench unfinished. In a few months it will weather to grey.

Final assembly was outside because the bench is more than five feet long. Within minutes my wife and I had bench-tested...er, tried it out, and guests gave it a trial sitting that evening. We all declared it a success. It's nice to see how the bench gives life to an overlooked spot. Today the locust bench sits about a hundred yards from where its wood grew, inviting us to enjoy the outdoors.