|

|

The Sharpening Process and Methods That Work:

How Lap-Sharp™ Compares

by Don Naples

Wood Artistry, LLC

The sharpening process is a topic frequently

discussed among woodworkers. When demonstrating the

Lap-Sharp

, we are often asked about other sharpening systems or methods and how

they compare to the Lap-Sharp. Frequently we are told of methods

or information that is useful to woodworkers, but also some that

is misinformation. This misinformation frequently causes woodworkers

to have difficulty in achieving the sharpening results they want.

They then assume it is an error in their approach, when it is actually

a process error. This document is intended to answer the questions

we most frequently hear, to provide sufficient data to qualify the

information provided, and to help woodworkers sift through the methods

and machines so they may come to a conclusion of what will work

best for them.

My recommendation to any woodworker is to

note the data provided, consider what seems logically correct or

shows proof in concept, test the methods to see what works for you

and then use the method you prefer repeatedly to gain expertise

in achieving the level of sharpness you desire. What is sharp for

one person may not be sufficient for another. Woodworkers have different

tools, some of which may not hold a really fine edge that tools

with a different type of steel will. The type of work, species of

wood being cut, and figure of the wood grain should all be considered

when sharpening. The test I apply to a plane iron is to sharpen

to a point that one may achieve shavings of about .001 (one-thousandth)

of an inch. This provides excellent performance with a smoothing

plane on figured woods and also works well with other planing.

Scary Sharp -

Not So Scary and Not So

Sharp

This method is widely promoted and does work to a point. It can

be made to work even better if one understands how it works and

its limitations. There is enough information readily available about

this method that I won’t repeat it here other than to state the

basic features. It consists of progressively finer wet or dry abrasive

applied to a flat surface which is then used as a honing surface

and abrasive. Here are some reasons why this method does not work

well:

-

One step in the process recommends applying an adhesive spray

to the underside of the abrasive paper and then applying it to

the flat surface (usually a thick glass). This will hold the abrasive

in place, but at the risk of creating small bumps from uneven

coating of the adhesive. It is important to keep the glass very

clean as any particles trapped on the surface of the glass will

also cause bumps. Either of these flaws will cause less than optimal

results when sharpening.

-

Another approach is to wet the back of the paper and use the

surface tension created when applied to a flat surface to hold

the abrasive in place. Anyone who has tried this has eventually

seen the paper move and at the wrong time, causing a cut or tear

in the abrasive that must be worked around when continuing the

sharpening process. In addition, a small wave can occur with the

pressure of the tool against the abrasive surface. This wave can

cause rounding of the edge and tips of the tool.

-

The abrasive used in wet or dry paper has a grit consistency

of about 55 percent. This means there is a mixture of pebbles

and boulders (relatively speaking) that are used to attempt to

create a smooth cutting edge.

-

Silicon Carbide is the abrasive used in wet or dry paper. It

breaks down very quickly, and then begins to burnish the metal.

It is not a useful abrasive for removing any significant amount

of metal. If the back of a plane iron has a rolled edge, using

silicon carbide paper will use reams of abrasive to achieve a

flat surface. This is one of the main reasons this sharpening

method causes such difficulty in achieving the desired results.

To prove this point, rub a steel tool on some wet or dry abrasive.

After a half a minute, look at the surface. You should see it

is beginning to shine. Now take a fresh sheet of abrasive of the

next finer grit and take one or two swipes with the tool where

you previously abraded the surface. You should now see fresh scratches

in the previously shiny surface. The initial abrasive broke down

quickly and began to polish the metal. The new but finer abrasive

will then cut through the polished surface and it too will quickly

break down. This is why it is difficult to sharpen with this method.

If the tool was previously flat and sharp, a few swipes of wet

or dry paper can reestablish a reasonably sharp edge, though not

as sharp as is possible.

-

A better approach with Scary Sharp is to use Aluminum Oxide

Micro Finishing Film. It has a grit consistency of 98 percent,

does not break down as quickly as Silicon Carbide, is available

in sheets from 100µ(150 mesh) down to 9µ(800 or P2000 mesh*),

has a 3mil film backing (for flatness), and may be used with or

without water.

-

When sharpening at the 10µ level and finer, take extreme

care to keep the abrasive clean and free from abraded material

and worn abrasive. If a buildup of abraded material occurs, it

creates lumps that gouge tracks in the surface of the tool being

sharpened. These tracks create a miniature serrated edge and will

prevent the tool from being as sharp as is possible. This issue

becomes more pronounced as you progress to even finer grit lapping

abrasives of 1µ and sub micron sizes. This is why the Lap-Sharp

is supplied with Trizact™ and polishing paper at the finer grit

levels. Trizact must be used wet, but does an excellent job as

the abraded material falls into the valleys of these apex structured

abrasives, thereby staying out of the way of the sharpening process.

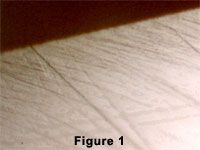

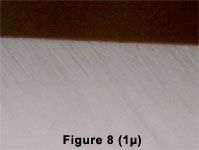

Figure 1

shows 200x magnification of tracks on a chisel

bevel after sharpening on a Lap-Sharp with 1µ lapping film

. The lumps of abraded material caused the gouges in the surface.

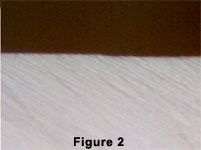

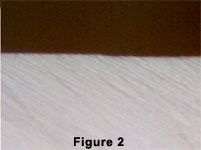

Figure 2

shows the chisel bevel sharpened on a Lap-Sharp

with 5µ Trizact without deep gouges.

-

Never use cloth backed abrasives for flattening, as the cloth

will compress and cause a rounded edge. This rounded edge may

also be created with wet or dry abrasive or water stones and is

one of the most common reasons woodworkers do not achieve the

desired performance of their tools. Often, one will use a tool

that works rather than the correct tool that does not work as

well. When looking at the reason for a poorly performing cutting

tool, this fault is most frequently one of the culprits.

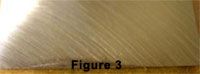

Figure 3

is a plane iron that has been sharpened by

a woodworker (not me) with the Scary Sharp method. I then put

it on the Lap-Sharp and abraded the back until the scoring was

even across the back, but had still not removed the worst part

of the rounded edge. The Scary Sharp method would take a long

time and much abrasive to remove this flaw, even if it did not

introduce additional flaws in the process.

Lap-Sharp Compared to a Wet Stone Grinder

The Lap-Sharp excels in providing flat honing of woodworking tools.

Laminated tools such as Japanese chisels and plane irons as well

as laminated cast steel plane irons should not be hollow-ground,

as the hard steel in laminated blades is brittle and may more easily

chip if hollow ground. Likewise, carving tools are not hollow ground.

Hollow grinding western style plane irons and chisels is acceptable,

and some prefer it as it reduces sharpening time when using a manual

method of honing steel tools. Hollow grinding creates a weaker edge

to the tool as the cutting edge is thinner. This edge will require

more frequent sharpening, as the thinner steel edge flexes and wears

more quickly. This is especially true when sharpening planer or

jointer knives. These knives are then used with motor driven machines.

I know of no manufacturer that produces planer or jointer knives

with a hollow grind.

-

A wet stone grinder cannot flatten the back of a tool. Some

attempt to do this by holding the tool onto the side of the wheel.

There is no provision for flattening the wheel side surface; the

finish is limited to the abrasive grit of the wheel. Assuming

a 220 grit wheel, you will have a 60 micron finish on the back

of the tool - far too coarse for use as a cutting tool. The scoring

left from the wheel leaves a serrated edge.

-

When wet-grinding the bevel edge, some wet-grinders use a filler

to reduce the coarseness of the wheel and create a quasi-finer

abrasive. To return to the original grinding capability of the

wheel, one must dress the wheel with a tool which wears away the

stone. After a number of times of doing this, the expensive wheel

must be replaced.

-

Some wet grinders recommend stropping the hollow-ground tool

on a leather wheel dressed with a polishing compound. This stropping

rounds over the edge of the tool. On a bench plane a rounded bevel

severely reduces the ability to work properly and fine shavings

are not possible. A rounded back edge of a block plane causes

similar poor results. You can still shave the hair on your arm

or cut a piece of paper but the edge that produces fine wood shavings

in a plane will be compromised.

-

When using a wet grinder, you will achieve a finer cutting

edge by using water stones or oil stones to finish the sharpening

process. With the stones, the back can be flattened and the bevel

edge refined to have a sharp finished edge.

-

The Lap-Sharp may be used wet or dry, (1) provides a flat grind

so it can flatten the backs of tools and sharpen both western,

Japanese, and laminated cast steel tools, and sharpen carving

tools, (2) has interchangeable discs of a wide range of PSA backed

replaceable abrasives to 1µ (finer than an 8000 grit [1.2µ]

water stone), (3) provides a polished edge that requires no stropping,

(4) does not require additional manual sharpening to achieve a

finished edge, (5) and is comparably priced with a wet grinding

system.

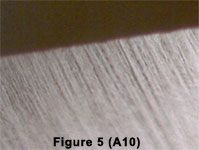

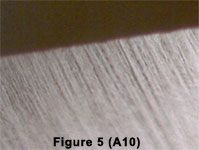

Figure 5

sharpened on a Lap-Sharp with 10µ Trizact.

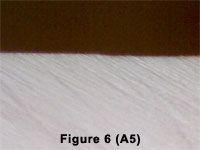

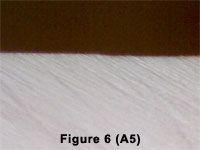

Figure 6

sharpened on a Lap-Sharp with 5µ Trizact.

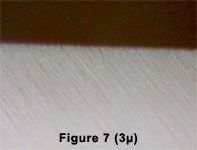

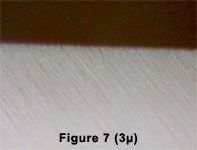

Figure 7

sharpened on a Lap-Sharp with 3µ Polishing

Paper.

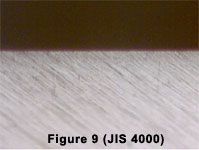

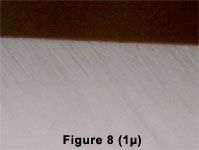

Figure 8

sharpened on a Lap-Sharp with 1µ Polishing

Paper.

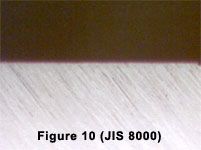

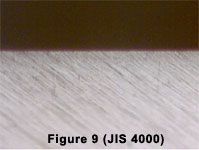

Figure 9

sharpened with Japanese Kingstone.

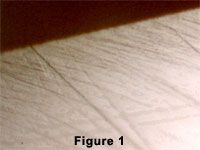

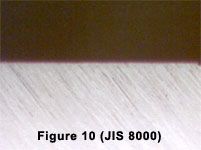

Figure 10

sharpened with 8000 Grit Japanese Waterstone.

-

In addition, the Lap-Sharp:

-

Requires no soaking of the abrasive or removal of water

tray to prevent softening of wheel.

-

Requires no dressing of a wheel to remove grooves, flatten,

or to change back to original grit.

-

Is foot switch activated so one can position the tool in

place with both hands prior to starting the abrasive rotation.

-

Is also slow in rotational speed (less than 200 RPM) to

avoid significant friction heat and provide easier control

of the tool being sharpened especially when items are hand

held.

-

Is direct drive and uses needle bearings, so no belts to

adjust or replace, has less vibration, and does not depend

on a friction created by a small rubber wheel that is pressed

against a larger plastic one.

-

Can quickly sharpen the flat sides and edge of hand scrapers

(one must still roll the burr).

-

May be used as a stationary sander for small projects including

fine adjustments of angles on wood blocks used in segmented

bowl turning.

-

Has a larger surface area than grinders so an even edge

may be more easily achieved.

-

Can flatten the soles of small planes and other objects.

-

Rotation of the motor is reversible so it may easily be

used to sharpen knives and create even wear on hand held flat

items, and can sharpen the flat side of profile shaper knives.

-

Has a planer/jointer jig option that performs a flat grind

on knives to 25 inches in length.

-

Has an optional jig for turning and carving gouges that

enables one to achieve very sharp tools quickly and without

removing much of tool’s steel in the process.

-

Has diamond and CBN abrasives available for hard metal

and carbide tools.

-

Is constructed with a cast aluminum housing that provides

a stable platform that does not tip.

|

|