|

|

The

following article was originally published in

Wood News

No.

16, Fall 1985.

Japanese

Woodworkers

by Tom

Frazer

In

Kyoto, Japan, a few supreme artisans such as woodworker Isaburo Wada

still ply their craft in a timeless tempo known as "Kyoto

time".

For more than a thousand years, Kyoto was the capital

of Japan. As such, her rulers attracted the most skilled artisans,

and slowly, over the centuries, the city became a repository of the

highest expression of artistic endeavor.

By good fortune, I

was invited to Japan last fall by that country's Ministry of Foreign

Affairs and was able to meet Wada and other Japanese woodworkers, as

well as most of the master toolmakers of Miki City.

And

indirectly from Wada, I learned the meaning of "Kyoto time". It went

like this:

And

indirectly from Wada, I learned the meaning of "Kyoto time". It went

like this:

Wada is the sixth generation head of Enami Co., Ltd.,

a company that has specialized in textiles and traditional Kyoto

joinery for 200 years. It is the oldest Kyoto joinery firm still in

business. As he showed me through his multi-story workshop, a large,

donut-shaped piece of wood caught my eye, and I asked Wada what it

was.

"It's going to be a traditional hibachi," answered Wada.

Then glancing at his homemade lathe, he commented, "I could have

turned it on that machine in five minutes, but I wanted to shape the

wood the old-fashioned way, by hand planing. But you must shave off

only a small amount at a time. Otherwise, the wood will

crack."

"How long have you been working on it?" I asked in all

innocence.

"Ten years," responded Wada. "And the wood was aged

ten years before I began work."

Wada, official boxmaker to

the Emperor, thus knows how to work according to "Kyoto time", a

timeless time in which an artist works to utter perfection, his

attitude uncluttered by any other earthly consideration.

But

don't imagine that Wada is simply a cobwebby throwback to

yesteryear. He is a tireless experimenter, and uses everything from

outdoor weathering to chemicals and a kiln to stabilize the shape

and color of wood. Although he has achieved 20-year stabilization,

Wada nevertheless is dissatisfied and says he is trying to do even

better.

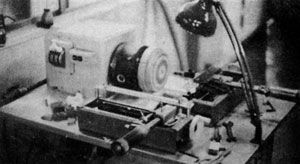

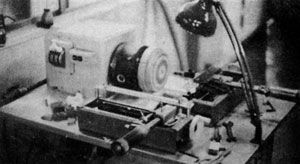

He is particularly proud of an elaborate wood lathe

he designed and constructed of aluminum, welding it himself. The

lathe is used chiefly for making wooden bowls, and because Wada

wanted to make it easier for apprentices to duplicate a given shape,

he designed his own screw-feed bit arrangement, very similar to that

of a mctalworking lathe. Instead of employing a hand-held turning

tool, an apprentice can turn handscrews to feed the cutting

bit.

But Wada's crowning achievement with his lathe is his

own novel design which permits the workpiecc to be held onto the

chuck by vacuum supplied by an electric air pump. Without screws or

chuck jaws, Wada pointed out, the wood cannot possibly be

damaged.

Without doubt, Wada's dogged pursuit of artistic

achievement resulted in his being designated a kyo-sashimono, or

traditional craft joiner, by the Japanese government in 1977. Three

years earlier, Wada made 36 boxes for the Ise Shrine, the holiest

shrine of Japan's native Shinto religion. (Showing a spirit

remarkably different from the builders of the pyramids, officials

responsible for the Ise Shrine order the sacred wooden complex torn

down and painstakingly rebuilt at 20 year intervals.)

Wada

and his ten apprentices specialize in handcrafting exquisite

small-to-medium sized objects of wood, such as intricate boxes,

bowls, screens, trays, lamps, inkstone containers, spoons, tables,

chests and shelves.

Wada and his craftsmen use some 35

varieties of hardwood and softwood, although he said about sixty

percent of what he uses is paulownia. He described it as "the

lightest and softest wood in Japan."

Years ago, Wada said,

paulownia was exported to the United States where it was planted as

a shade tree. But since no one used it for any other purpose, he

said, the Japanese are now importing it back to Japan. "It has a

cell structure similar to grass and only grows a maximum of about

eighty years, like a human being," said Wada. "When it reaches forty

to sixty years, that is the best time to take the tree - also the

best age for a craftsman to produce his best work." said

Wada.

The kyo-sashimono is so determined to preserve

traditions that his workshop still can turn out an incredible 7500

different wooden objects of traditional Kyoto design. In many cases,

the objects are made in exactly the same manner that craftsmen made

them 1000 years ago. Sometimes, over the centuries, the designs

evolved minutely. For instance, items made for the Ise Shrine

included a box-like container crafted from peeled willow switches to

hold cups and slippers. According to Wada, the original containers

were tied together with strips of willow bark. Now he uses silk

thread to copy the newer, current design.

Although Wada

employs the use of some power tools, traditional Japanese hand tools

account for the bulk of his shop's craftsmanship. His company

possesses a collection of some 45,000 hand tools, among them planes

between 200 and 400 years old.

Wada's apprentices sit at the

lower end of slanted, thick cherry planks that serve as workbenches.

Only a small wooden stop set into the plank at the apprentice's end

adorns the workbenches. Traditionally, said Wada, craftsmen sat on

cushions on the floor and bent over their work. But because bending

for long periods can hurt the back, Wada has arranged for the

workbenches to be elevated and his apprentices now sit on low

stools.

For himself, Wada reserves a small room for his

private workshop. He sits on a cushion and works under a solitary

hanging lamp. On the tatami mat within easy reach are a variety of

marking gauges, chisels, saws and planes. More saws and planes rest

in wall racks.

For an interested visitor, Wada will pluck

several ancient tools from their special places and display them

reverently. He explains that the small saw and the worn chisel were

made from very special blue steels, which enable them to hold their

sharpened cutting edges longer than the tools available today. Wada,

a traditionalist, treasures their exquisite quality.

Another premier Kyoto woodworker is Kenkichi Kuroda,

the teacher mentioned by Charles Roche, his former student who wrote

about Japanese lacquer in the March '85 issue of Fine Woodworking.

Thanks to Howard Lazzarini, another former student, I was able to

meet Kuroda, who specializes in lacquered wooden

trays.

Lazzarini, both guide and translator, explained that

Kuroda is unusual in Japan because he both crafts the trays and

applies the lacquer. Normally, he said, craftsmen concentrate on

either one or the other.

A lacquered tray measuring roughly

12 by 18 inches requires an "absolute minimum" of a month and a half

to complete, said Lazzarini, adding that prices run in the vicinity

of $500 to $600.

Incidentally, Lazzarini recalled that during

the first three months of his apprenticeship, he was restricted to

sharpening tools. "Regular" Japanese apprentices, he said, begin by

sharpening tools for six months before being allowed to move

forward. During this time, Lazzarini said, he also made his own tiny

finger planes, shaping the metal blades as well as the wooden

bodies.

Kuroda often uses an elm-like wood called zelkova

with a very pronounced grain pattern. Moreover, he clearly is a

"wood freak" equal to any of us. In one room of his house he proudly

shows off huge, thick planks of a wood that translates as "horse

chestnut". It is shot through with a highly-figured, burl-like

pattern. Looking fondly at his precious wood, he joked with a smile,

"My friends say they are anxious for me to die."

Kuroda,

according to Lazzarini, is a philosopher (or philosophizer) when it

comes to wood. "He feels that there is a proper way to use wood. And

wood from a 500- or 600-year-old tree should be used in a special

way."

Speaking for himself, Kuroda said, "In today's Japanese

society, it is important to have automated things. Japan is

concerned with fads, and right now, handicraft is 'in'". But Kuroda

warned, "That is not a good way to approach wood. It is better to

really work with your soul - not because it is a

fad."

Lazzarini recalled that during his apprenticeship,

Kuroda "told us to treat wood with reverence. He told us that good

pieces are rare." Furthermore, Kuroda rejects the idea that human

beings are somehow "above" things such as wood, Lazzarini said.

"Kuroda holds that wood also has a spirit and that people should

treat wood with the same respect that they treat other

people."

The lacquer traditionally used by Japanese

craftsmen, incidentally, doesn't come from a can. It comes as thick

brown sap from the Urushi tree, and frequently produces a rash like

that caused by poison sumac. After someone works with the sap for

some time, he generally becomes immune to it. But Kuroda said that

even after years of using lacquer, he sometimes gets a rash on soft

portions of skin, such as between his fingers and behind his

ears.

One of Kuroda's prize possessions is a lacquer brush

given to him by his late father, one of Japan's elite "Human

National Treasures". The brush is 300 years old and is made from

human hair. Kuroda confides that many Japanese lacquer craftsmen

believe the best brush hair comes from fishermen. "But some argue

for women's hair", he added. Japanese craftsmen seem to cherish such

small points.

When I told Lazzarini that I found ripping with

a Japanese-style saw awkward because of the shape of the teeth, he

responded that Kuroda takes both his saw and the wood he intends to

cut to a sharpener, and instructs him to sharpen the teeth

appropriately for that particular type of wood!

|

|