|

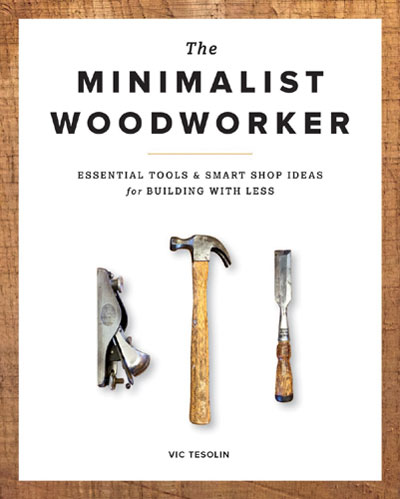

The Minimalist Woodworker

by Canadian woodworker Vic Tesolin is both a good introduction to

setting up a hand tool woodshop and a fun read. Its central message is to not let

anything—a lack of space or a limited set of tools—stop you from pursuing a passion for

crafting things from wood. Tesolin shows how a shop can be set up even in extremely

limited space and what tools are essential (and which are not) to start woodworking.

His focus is on hand tool woodworking, which needs neither to be unduly expensive nor

to require an extensive array of equipment.

Well–illustrated with numerous color photographs and drawings, the book is written in a

personable style that makes it readily approachable to woodworkers at all levels.

Though it contains much valuable advice and instruction, it's nonetheless a quick read

and one that will be well–appreciated by those who are more eager to get started than to

wade through long introductory treatises.

The opening chapter urges using the space you've got, rather than longing for a perfect

(i.e., larger) space. You can, he asserts, work anywhere, and he documents a number

of examples, including his present garage workshop, a previous shop under his

staircase, a utility room shop and even a woodshop in a living room like the one

operated by my friend Mike. Whatever space you decide to use, good overhead and

task lighting are essential, as are heating, cooling, humidity control and ventilation.

Wood flooring is ideal if you can manage it, but anti–fatigue mats are also useful to

sustain long work sessions.

The following chapter considers tools. Tesolin recommends a much smaller tool set for

starting out than many other authors do and he offers sound guidance on which tools

are essential. These include planes, saws, measuring and marking tools, boring and

fastening tools, chisels, and other tools, including some tools he considers optional. He

offers advice on setting up and adjusting handplanes, a simple process that new plane

users often find troubling.

Chapter 3 is devoted to measuring and marking, a basic requirement for accurate work.

Tesolin advocates measuring off the workpiece rather than the ruler as a way to

minimize errors. A marking knife, he says, will give you more accurate results than a

pencil. At the same time, knife lines can be used to chisel out saw guides to enhance

cutting accuracy with a saw. He explains how to use a combination square properly to

check a board for squareness and how and why to use carpenter's triangles to mark

individual project parts and reference faces.

The next chapter examines sharpening. Tesolin describes how to polish and hone

chisel and plane blades, the angles he uses and the equipment he recommends,

including a sharpening bucket he designed that will ease sharpening and aid in shops

that lack running water (like mine).

In chapter 5 Tesolin describes the construction of a saw bench and saw bent—a

sawhorse that matches the level of the saw bench to support long boards while they are

being cut. These are shop–made tools he considers essential to support subsequent

work in the shop. He bores dog holes in his sawbench top and adds a fence on one

side—an unusual feature—so the bench can be used for a variety of operations besides

crosscutting and ripping boards.

He then shows how to build a shooting board hook, a device that combines two

appliances—a shooting board and a bench hook—into one by setting the shooting

board fence into a dado so it can be easily removed and replaced. It's a creative idea

for working with less gear in a small and efficient shop.

Tesolin demonstrates how to make a wooden mallet with leather covering one end,

another useful shop tool. More important, though, is the Nicholson–style workbench he

builds using home center lumber, which he regards as quite adequate in strength and

durability. He describes the methods and appliances he uses to hold wood in position

for planing, chiseling and other operations, and he shows how this can be done without

the need for a vise.

The final project is a small shelf to house his set of essential shop tools. He chooses

oak for the shelf to make use of its strength in bearing the weight of sometimes heavy

tools. One innovative idea is using wine bottle corks as pegs from which to hang saws

by their handles. The soft cork prevents damage to the handles that might otherwise

occur through scratching.

The book's principal strength is its advice on setting up a workable, if small, workshop

and in its exhortation to let no lack of resources stand in your way. In addition, the

projects outlined in the book will help beginning hand tool woodworkers to build their

skills through experience.

This book is especially appropriate for woodworkers who are just getting into the craft

and those who are converting from a power tool–oriented style of work to one centered

on greater use of hand tools. Besides that,

The Minimalist Woodworker

is a fun book to

read and one that I especially enjoyed devouring.

Find out more and purchase

The Minimalist Woodworker

J. Norman Reid is a woodworker, writer, and woodworking instructor living in the Blue Ridge Mountains with his wife, a woodshop full of power and hand tools and four cats who think they are cabinetmaker's assistants. He is the author of

Choosing and Using Handplanes

.

He can be reached by email at

nreid@fcc.net

.

Return to the

Wood News Online

front page

|